Brandon Perry was experienced and his boat was well prepared for the 170-mile offshore delivery.

When Brandon Perry left North Palm Beach, Florida in a 31-foot center console boat, he had every intention of reaching Treasure Cay in the Bahamas that night. It was a simple trip; he was delivering the boat for a friend. In the course of his 25 years of boating, he had made the trip 100 times before on boats of this design and size.

Boating was a family activity while growing up on the Florida coast; each of the steps he made in preparation for the trip came from rote memory and could be performed almost without thought. The boat was ready. Supplies were stowed. The fuel and water tanks had been filled. To Brandon, the trip wasn’t much different from a road trip to a visit a college buddy for the weekend—and someone else was picking up the gas bill.

But little did he know this wasn’t going to be a smooth road trip.

Normally a Safe Route

From North Palm Beach Treasure Cay is about 170 miles away and usually takes boaters six hours to complete the journey. It’s done by boaters with a wide range of experience in everything from Sportfishers to small open center console outboards—there is even a group of jet skiers that make a trip to the Bahamas on an annual basis. The seas are normally calm enough for 30-foot open boats to make the journey safely cruising at 30-40 knots allowing boaters to outrun possible storms.

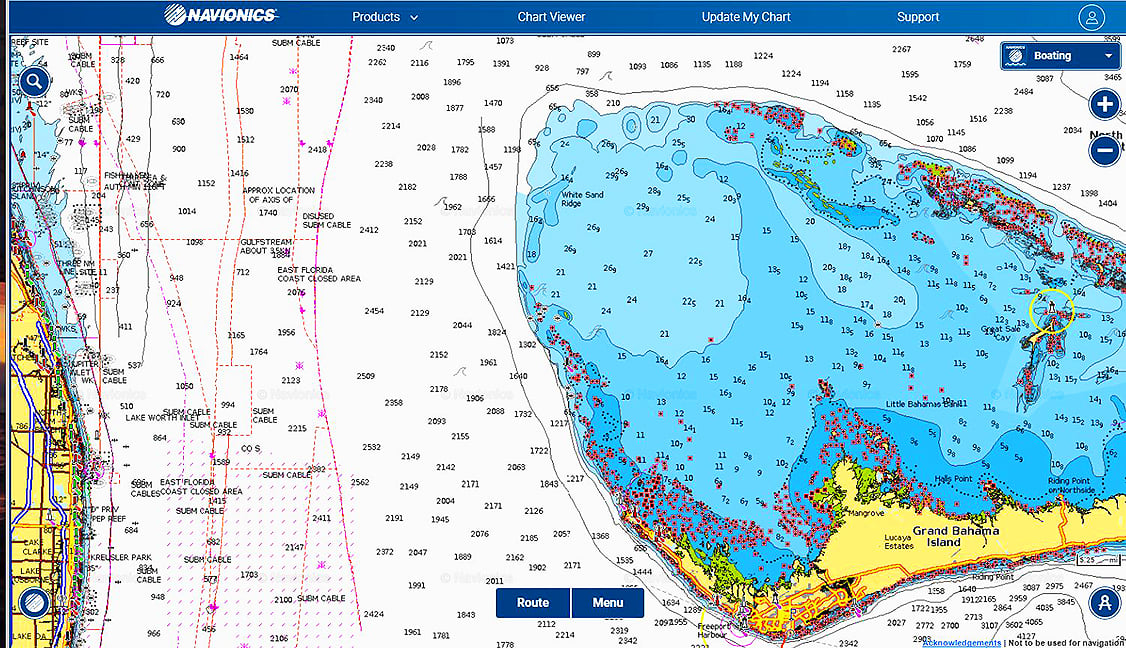

Brandon's route from North Palm Beach to Treasure Cay. He made it about as far as the yellow circle on the right.

The Jupiter 31 Brandon was taking to Treasure Cay was more than enough boat for the journey. The deep V hull quieted the chop while tall topsides kept passengers dry even in moderate waves. Twin outboards sipped fuel from the tanks that offered a range well over 170 miles. Compared to the jet-ski club’s trip, this was going to be luxurious.

The night before the trip, Brandon picked up the boat from a yard after some repairs had been made. In the morning, he ran the boat on a shakedown cruise to go through the systems and familiarize himself with the boat. The three-hour-long ride offered no indications of trouble. Everything ran as expected. An inventory of the boat’s equipment and tools revealed the lack of an Emergency Position Indicating Radio Beacon (EPIRB).

The Jupiter 31 center console

Borrowing a Friend's EPIRB

Having always traveled with one, Brandon reached out to a friend to borrow his ACR GlobalFix™ Pro EPIRB to take on the trip. He picked it up, then proceeded to load all of the gear headed to Treasure Cay and fill the fuel tanks. A check of the weather revealed a small storm moving in but the Jupiter could easily outrun it with the seas as calm as they were. Even if the storm did catch up, it wasn’t expected to be of any consequence.

With the final checks made, Brandon set off to Treasure Cay at two in the afternoon.

Skipping along the water at 40 knots the Jupiter was making great time—even loaded with a wheelbarrow, tires and household items destined for the boatowner’s house in the Bahamas. About three quarters of the way to the Bahama Bank, the engines began to act up. Then the electronics.

Losing Both Outboards

Brandon backed down a little to try to figure out what was going on and at that point both outboards died. There was an eerie noise from the outriggers. Brandon’s assessment was that he had ventured into a statically charged area that had just been hit by lightning or was about to be. The static energy had wiped out the electronics and caused the fuel tanks to vacuum lock, leaving him adrift.

Eventually, after employing his understanding of the twin Yamahas, he was able to get one of the engines running and adjusted his course to the nearest landfall: West End.

The trip had significantly changed at this point. He was running on a single engine, unable to get up on plane, and reduced to slogging along at seven knots painfully into four knots of current. Brandon was going nowhere fast and the storm he hoped to outrun was catching up with him. The wind began to pick up, then the seas.

The Weather Deteriorates

Darkness was about to fall and the seas had grown to 6-8 feet with wind gusts around 30mph. The storm was pushing him further from West End. Another evaluation of the situation led him to change course yet again to Great Sale Cay, hoping to get out of the weather.

“I readjusted my course and prepared myself for what would end up being the longest night of my life,” Brandon added.

Brandon continued to labor toward Great Sale Cay in hopes of some relief from the storm that had engulfed him and to have another crack at restoring the disabled engine. High winds continued, with driving rain and lightning followed by giant claps of thunder. Waves were beginning to crash over the bow and flood the deck beyond the capacity of the scuppers and bilge pumps.

At 2am, 12 hours into the journey, the weather began to show signs of relief. The winds had calmed and the rain had let up, but the seas were still stirred up from the power of the storm. For another couple of hours, the Jupiter limped along and was approaching Great Sale Cay when the only working engine began to act up again.

Exhausted and somewhat defeated, Brandon reluctantly made the call to drop anchor and recharge by attempting to get some sleep.

A Waterspout

The GlobalFix™ Pro EPIRB that Brandon activated when all other means of rescue were exhausted. The EPIRB was purchased at West Marine's North Palm Beach store.

“Ten minutes into my sleep, the weather was shifting in a way that would alarm any mariner. The wind died down for a moment, which I found odd. I got up from the deck and looked up at the clouds. What I saw was the start of a waterspout.” Brandon noted.

Brandon’s sleep was short lived. Quickly, he grabbed the EPIRB and took shelter in what little space was available among the dish soap, toilet paper and canned goods under the center console

“It [the water spout] ripped around and across the boat for what felt like an eternity,” he said. Brandon remained hunkered down in the center console until daybreak—about two and a half hours later.

Running Out of Options

With the morning light, he quickly began to explore his options and looked for new ways to fix the engines. Every possible option for repair had been exhausted. Feeling defeated once again, Brandon turned to the VHF to connect with another boat in hopes to relay a Mayday to the U.S. Coast Guard. But there was no response. He tried his cell phone, but both the mainland and Bahamian cell towers were out of range.

Brandon was reluctant to activate the EPIRB at first—he didn’t want to alarm family and friends. But after evaluating the circumstances, it was the right thing to do. He assessed the weather and sea conditions and concluded the possible search area was rapidly growing. His chances of being rescued were diminishing quickly.

Brandon activated the EPIRB.

A Long 40 Minutes

A Coast Guard cutter was within 15 miles of Brandon’s coordinates and arrived at the Jupiter 40 minutes later, after what Brandon described as a very long 40 minutes.

“Mentally, when you have triggered the EPIRB, you are ready to be saved,” he added.

Here are Brandon Perry and Savannah Burdette after a happier day of fishing. In his 25 years of active boating, Brandon had made this trip about 100 times without incident, until now.

Normally when you read a survival story, the survivor is an ill-prepared individual who takes a risk—or a series of risks—that lands them in a dangerous situation and forces them to send up a flare and wave the white flag of surrender. Brandon was not that type of survivor. He had relied on years of boating experience and the countless similar trips he had made to stack the deck in his favor before setting off from North Palm Beach.

Ultimately, he owed his survival to his forethought in borrowing an EPIRB when he realized the Jupiter wasn’t equipped with one.

“I truly believe that having the EPIRB is what saved my life.”

Many boaters—too many—do not own locating beacons and don’t think to take one along; these are the survivors who normally make the headlines. Using Florida as an example, only 15% of the registered recreational vessels have an EPIRB, according to ACR (based on the DMV number of registered boats in Florida vs NOAA number of registered beacons in Florida). It is important to note that Florida has more registered recreational vessels than any other state in the US: a record they have held for at least eleven years.

Cost is cited as the common hurdle to having some form of beacon aboard. Putting aside the cliche that you can’t put a price on your life, EPIRBs are relatively inexpensive. Most fall into the same price range as the popular coolers we all have on our boats and wouldn’t leave the dock without. While modern coolers will offer some flotation to cling to in an emergency, they offer little to no help in coordinating a rescue

The other hurdle is the struggle boaters have with shelling out money for a piece of equipment they hope to never use because it’s easier to rationalize the expense of keeping your beer cool for tomorrow’s trip than to have your life saved in six months, a year, maybe two years.

Fortunately, Brandon understood the value in having an EPIRB and made it a point to have one for what was normally a routine trip. It saved his life, and that’s something money can’t buy! Just ask his family.